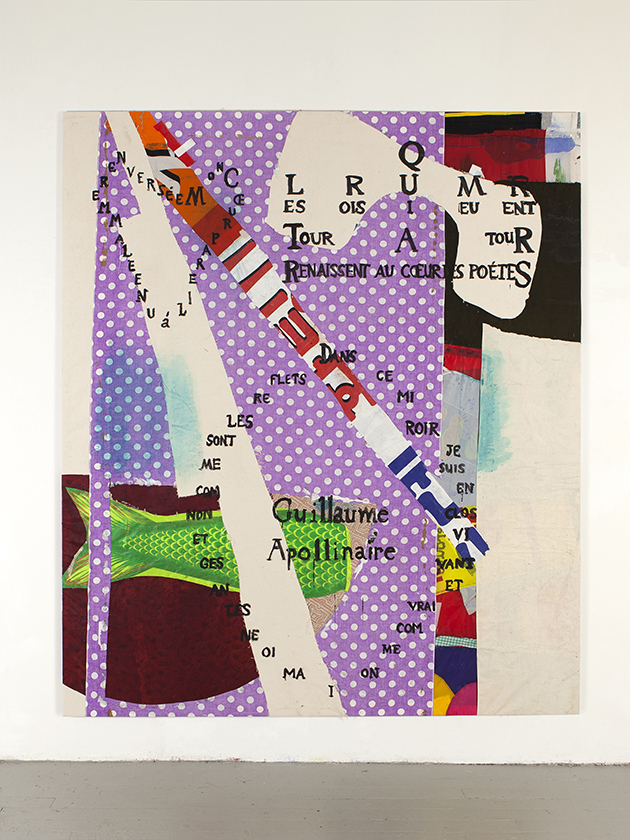

Contributed by Heather Bause Rubinstein / Joe Fyfe’s newest series of paintings at Nathalie Karg Gallery are packed with visual, poetic and intellectual punch. Fascinated by the possibilities of collaged-together textiles, Fyfe is pushing his work into more formal complexity. Also new is a recurring textual element: hand-painted enlargements of French poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s Calligrammes.

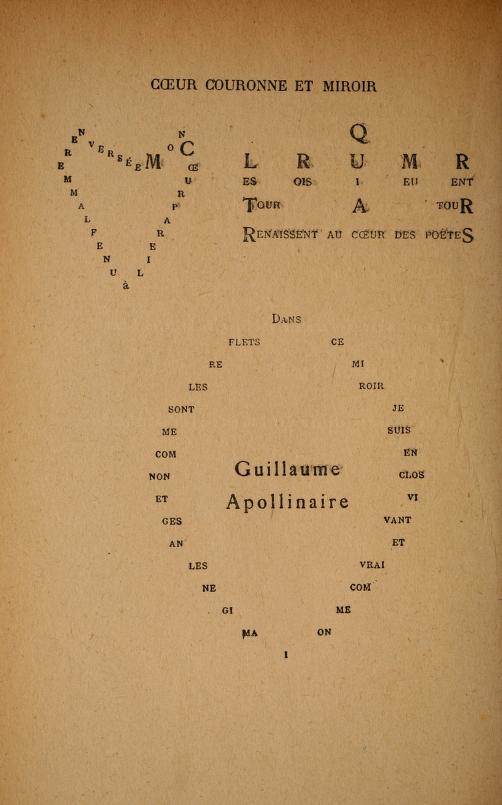

The engagement with Apollinaire seems a natural extension of Fyfe’s long-standing attachment to French culture (symbolized by a recent two-person show at Ceysson Bénétière in Saint-Étienne with Supports/Surfaces pioneer Claude Viallat). First published in 1918 (Fyfe was conscious of the centenary), the Calligrammes feature words, letters and phrases arranged in different layouts, often creating typographic images. In effect, Apollinaire transformed his poems into complex visual collages. The printed word —the printed page—became a field of experimentation. With the Calligrammes, the standard Western habit of reading poetry left to right, top to bottom, was no longer possible. (Of course, Apollinaire was building on Stéphane Mallarmé’s radical typographical experiment Un Coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard, published in 1897, twenty-one years before Calligrammes.) Through his playful use of typefaces and compositional arrangements, Apollinaire created poems that had to be both seen and read. This double functionality turned the page into a sort of canvas for the poet, allowing him to express himself through spatial relationships and multiple readings.

Fyfe echoes Apollinaire’s creation of double meanings, and on multiple levels. First, the paintings are lovingly constructed collage-paintings using bits and pieces of fabrics and textiles the artist gathered from around the world. As such, they can be read as contemporary collages repurposing present-day cultural-artifacts, while also looking back to Cubism, with which Apollinaire was so deeply involved. From this perspective, Fyfe’s paintings can be understood as distillations of 20th-century modern art and graphic design. As in some of Fyfe’s earlier work, the fabrics and textiles he folds into his paintings feature design elements that sometimes utilize text. However, with the layering of the Calligrammes onto the surface of these densely-packed compositions, something else happens as the poems take on a double role: the overlaid text unites the disparate fabrics underneath, while also paying homage to Apollinaire’s insistence on the materiality of written language, its existence as visual mark. And, of course, we can read the poems (if our French is good enough).

Ultimately, the overlaid poems are necessary to the work. Without them, the paintings risk coming across as beautiful if overly familiar examples of collage-based abstraction—instead, the interruptions, the shifts of scale and textual content from the Calligrammes propel Fyfe’s finished paintings into a privileged place, where poetry and painting fuse. Apollinaire would have been pleased.

“Joe Fyfe: But a Flag Has Flown Away,” Nathalie Karg, LES, New York, NY. Through February 10, 2019.

Bonus audio: Listen to a 1913 recording of Apollinaire reading his poetry on YouTube

About the author: Heather Bause Rubinstein is a painter, writer, curator and professor who divides her time between upstate Pennsylvania, New York City and Houston, Texas. Her work has been included in exhibitions at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, Greece; Pierogi Gallery, Site Brooklyn and MANA Contemporary in NYC; McClain Gallery, Devin Borden Gallery, Zoya Tommy Gallery, Gallery Homeland, the Blaffer Museum and RedBud Gallery in Houston; Galleri Urbane of Dallas and the Diary in Colorado. She recently c0-curated “Under Erasure” with her husband Raphael at Pierogi2000 in New York.

Related posts:

The backstory: Supports/Surfaces survey at CANADA

Unlimited: Painting and political upheaval

Dona Nelson: Exuberant overworking as a strategy

Two Coats of Paint is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To use content beyond the scope of this license, permission is required.